Minnie Minoso cleared path for other players

Sunday seven great baseball players spanning generations of accomplishment were inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. the 2022 class of inductees included David Ortiz, Tony Oliva, Jim Kaat, Bud Fowler, Gil Hodges, Minnie Minoso and Buck O’Neil.

All were deserving, although I have to admit that I had never heard of Bud Fowler. He was from an earlier time and while we think of Jackie Robinson being the one who broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball, Fowler was the first African-American to play “professional” or as it was often called when I was younger “organized” baseball. Fowler never made it to the Major League level, but played for a great number of teams. Usually, he was forced to move from community to community because of the blatant racism he encountered, not only in the South, but in places all over the United States. Teams hired him, because he guaranteed a large gate for at least one or two games as people came out to jeer him. He played his first game at age 14, and because minor league players’ salaries were a mere pittance, he made a living cutting hair where ever he went. He may or may not have been a good Major League player, but when he might have been good enough for the next level, the chance to prove himself at the top level of the game was taken away when MLB owners entered a “gentlemen’s agreement” in the 1890s that would exclude African-Americans from playing.

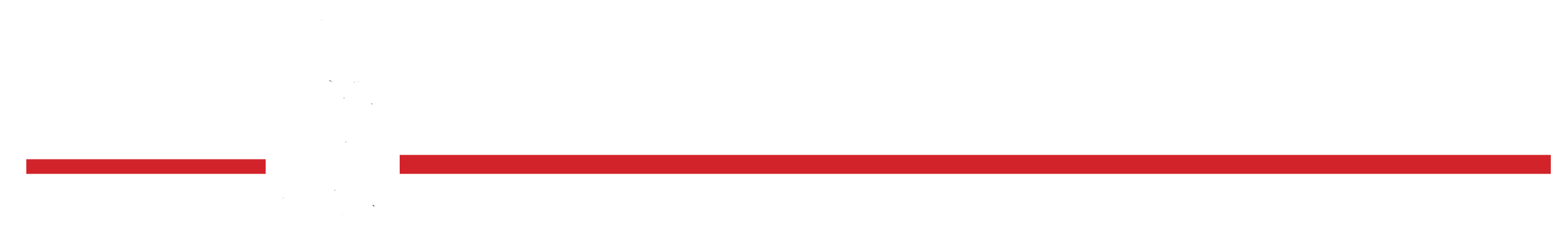

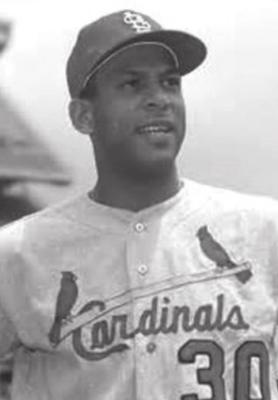

While I found Fowler’s biography to be interesting, I learned something about another inductee -- Minnie Minoso. Minoso had long been one of my favorite players. His name “Minnie” intrigued me as a youngster. Where I came from Minnie was a girl’s name, you know, like Minnie Mouse or Minnie Pearl. So, I was surprised when I found out there had been something about this gifted player that I hadn’t known.

What I learned was that Minoso was to Afro-Latino players what Jackie Robinson was to African-Americans. He broke a former barrier by becoming the first Afro-Latino to be accepted in the Major Leagues.

Minoso was born in Cuba and made it to the United States long before Cubans were not allowed to emigrate here. He played baseball for a while in Cuba and then after coming to the United States played in the Negro Leagues for the New York Cubans. When the MLB color barrier was broken, the Cleveland Indians signed him in 1949. He wasn’t able to break into a very potent Indian lineup and they traded him to the Chicago White Sox, where he found a home. People remember Ernie Banks as being “Mr. Cub.” Minoso was known in Chicago as “Mr. White Sox.” He spent a couple of seasons with Cleveland after having been traded there after the 1957 season and missed being a part of the Sox’ 1959 pennant winning team. But in 1960 he was traded back to Chicago, where he stayed the remainder of his playing days.

It was Tony Oliva, who in his induction speech lauded Minoso for being the one who blazed the trail for Afro-Latino players. Nowadays, there are many players who are in that category as places like the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico are hotbeds of great baseball. In Sunday’s HOF class Oliva and Big Papi Ortiz are two who followed in Minoso’s footprints. They would certainly qualify as being among the best in that special category to play in the MLB.

“Who are some other notable Afro-Latino players?” I asked myself. Thanks to the internet, the answers to today’s questions aren’t that difficult to find. The names that immediately popped up were Roberto Clemente (Puerto Rico), Juan Marichal (Dominican), David Concepcion (Venezuela), Oliva (Cuba), Ossie Virgil (Dominican), Mariano Rivera (Panama), Rod Carew (Panama), Ortiz (Dominican), Roberto Alomar (Puerto Rico), Orlando Cepeda (Puerto Rico) and Pedro Martinez (Dominican).

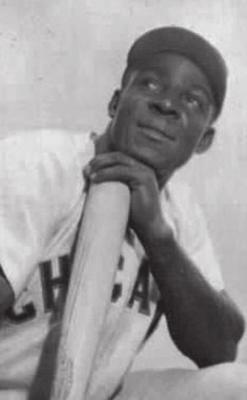

Clemente was a favorite of mine. I rooted long and hard for the 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates and he was a member of that team. He was a great hitter, and as an outfielder he had an amazing arm. I remember seeing him throw out base runners from his position in right field a number of times on television. He was a member of the All-Star team 15 times, was National League Most Valuable Player in 1966, was the NL batting champion in 1961, 1964, 1965 and 1967. On the last day of the 1972 season, he rang up his 3,000th base hit. His untimely death came after the 1972 season, in a plane crash. He was involved in delivering aid to earthquake victims in Nicaragua. He was only 38 at the time and undoubtedly could have had two or three more productive seasons.

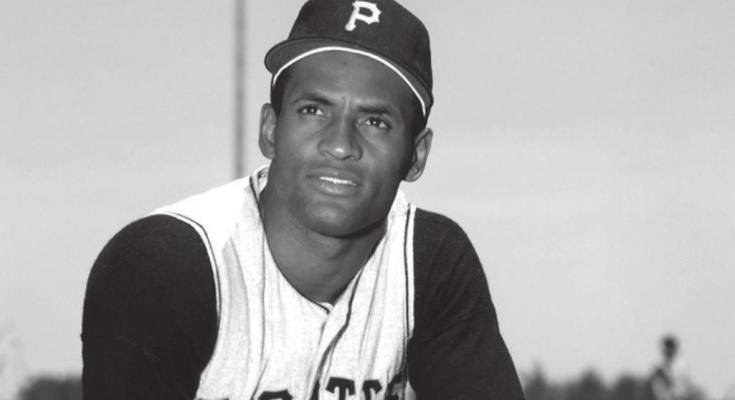

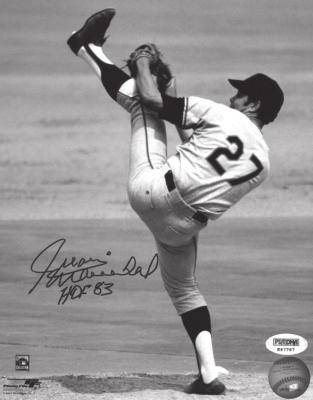

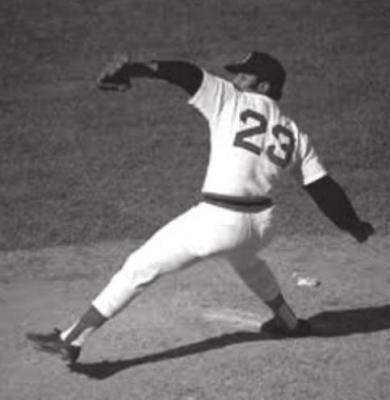

Another favorite of mine was Juan Marichal. He was known as the “Dominican Dandy” in his years pitching for the San Francisco Giants. I remember watching him pitch on televised Giant games and I noted his pitching style, which was some what unique. He had a high kick, which from the right side, compared nicely with the kick left-hander Warren Spahn had. Like Spahn, Marichal had a variety of pitches. He could throw a heater, but he mixed speeds and had a nasty curve to go along with a nasty screwball. I heard a YouTube interview with Pete Rose who called Sandy Koufax and Bob Gibson two guys who were basically unhittable. But he added the toughest pitcher for him was Marichal. “You had no idea what he was going to throw next,” Rose said. Marichal was an All-Star 10 times and led the league in wins in 1968 and in ERA in 1969. He pitched in the same era as Koufax and Gibson, who often received the postseason honors, But Marichal’s lifetime ERA of 2.89 gives an indication of how good he was.

Orlando Cepeda broke in in 1958, about the time the San Francisco Giants also had Willie McCovey. The two provided a great one-two batting punch for a number of years. Cepeda was known as “The Baby Bull” and in Puerto Rico was known as the son of “The Bull” Pedro Cepeda, a big name in that island’s baseball heritage. He was traded to St. Louis in 1967 and led the Cardinals to a World Series victory, earning the NL Most Valuable Player award. He later played for the Atlanta Braves, the Oakland A’s, the Boston Red Sox and the Kansas City Royals. As a member of the Red Sox he won the American League’s first Most Valuable Designated Hitter award in 1973. He was the first Latino to win home run and RBI titles in the MLB, which he did in 1961.

Ossie Virgil was yet another of my favorites. He broke into MLB in 1956 with the New York Giants. He wasn’t a great hitter, but he was a good defensive player and played just about every position during his career. He was known primarily as third baseman, but his versatility gave his managers a good backup at other positions. When he broke in with the Giants he was the first Dominican to play in the big leagues. Now a player from the Dominican Republic is fairly commonplace. He was traded to the Detroit Tigers in 1958 where he became the first black player in team history. So, he was a ground breaker of sorts. He bounced around some. After playing for Detroit, he had stints in Kansas City, Baltimore, Pittsburgh and San Francisco, where he closed out his playing days. He also contributed Ossie Virgil Jr. to the MLB as junior had a decent career of his own.

One whose name didn’t pop up in my initial search, but came to mind later was that of Luis Tiant. I loved to watch Tiant pitch. He had this most unusual windup, where it appeared that he was turning his head to look in center field before releasing the ball. Tiant was born in Cuba and his father Luis Tiant Sr. was a national hero, being an outstanding pitcher in his own right playing professionally in the U.S. Negro Leagues in the summer and in Cuba during winter months. Luis Jr. broke in with the Cleveland Indians and had a remarkable year in his second year (1968) when he led the league in ERA (1.60) shutouts (nine including four consecutive) and a 21-9 record. He later pitched for the Minnesota Twins, Red Sox, Yankees, Pirates and Angels before hanging up the spikes in 1982.

As MLB owes a great debt today to Afro-Latino players in the game, Minoso’s pioneering effort in becoming the first of his ethnicity to play, is to be celebrated. Yay, Minnie!