Personal library provides some gems

Editor’s Note -- This first appeared in this space April 20, 2020.

One of the benefits of staying at home these days has been an opportunity to reacquaint myself with my library. In doing so I came across a volume about baseball that I had forgotten -- “Greats of the Game: The Players, Games, Teams and Managers That Made Baseball History.” Ray Robinson and Christopher Jennison are the authors.

This book came to me as a gift a number of years ago and finding it made me feel as if I had received a gift all over again. My goal now is to share insights gained while rereading this book.

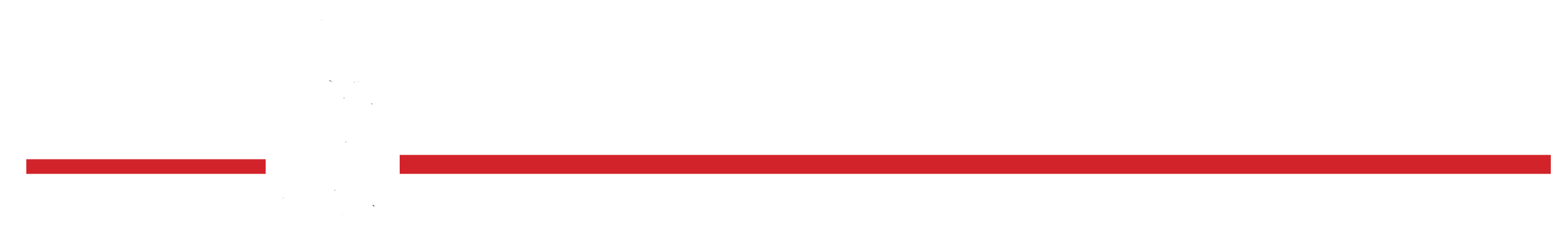

I came across a story about Carl Hubbell who was reared in Oklahoma, Meeker to be exact. As I have recounted over and over in this space, a lot of my early interest in sports was influenced by my father, who taught me many things. I do recall him talking about Hubbell. Dad was born in Oklahoma (near Ringwood) and he was very proud of his heritage. He was proud to tell me that Hubbell had come from the Sooner State.

The story that is recounted in the book has to do with a special performance of Hubbell’s in the second All-Star game. He struck out five of the best (of all time) hitters in the American League in succession.

Anyway, the writer sets up the situation saying that Hubbell, a member of the New York Giants, had been chosen to be the starter for National League. The game was in Hubbell’s home park (New York’s Polo Grounds). He got off to a rocky start as the American League’s first hitter, Charlie Gehringer singled and the second batter, Heinie Manusch, walked. With two on and no outs, the American League had something going. National League manager Bill Terry (who was Hubbell’s manager on the Giants and who also was playing first base), walked over to see if the left-hander was OK. After Hubbell assured him he was, he went on to prove it. He struck out Babe Ruth on five pitches and then struck out Lou Gehrig. Jimmy Foxx closed out the inning by striking out on three pitches. Hubbell had struck out three of the best hitters in all of baseball history. In the second inning he started the way he had finished the previous inning by striking out Al Simmons and Joe Cronin. Yankee catcher Bill Dickey broke the spell by singling with two outs. But Hubbell had turned out one of the best pitching demonstrations ever by striking out five consecutive future Hallof-Famers. After Dickey’s single, the American League batter was Yankee pitcher Lefty Gomez. Gomez was a great pitcher, but he couldn’t hit a lick. Stepping in to bat, he commented to Gabby Hartnett, the National League catcher, “You are looking at a man whose batting average is .104. What the heck am I doing here?” To put emphasis on his statement, Gomez struck out on three pitches to end the inning.

The thing I especially remember about my Dad’s description of the event was that Hubbell’s best pitch was the screwball. I had heard baseball announcers (Dizzy Dean and others) talk about the screwball. I had fantasies about being an accomplished pitcher and my hope was that I could master the screwball. I never did, in fact I am not aware of any pitch that I mastered.

Another great moment in baseball history is one that I experienced via the medium of radio. It happened in the first game of the 1954 World Series and wasn’t a moment I would have shared with Dad. World Series games in that era were played during the day and I would have been in school when it happened. My teachers usually turned on the radio during the World Series and allowed class members to listen, as long as we were relatively quiet. I don’t know how many of my classmates had the same affinity for baseball as I had, but few complained about the World Series being turned on. However, I do remember a complaint once from someone (obviously not a fan) who said “I hate football.”

On that day in 1954, I was rooting for the New York Giants to defeat the Cleveland Indians. I usually pulled for the underdog and the Giants were a decided underdog in the Series. Cleveland had won 111 games during the regular season and had one of the best pitching staffs in baseball history with Early Wynn, Bob Lemon, Mike Garcia and Bob Feller as starters. In the eighth inning of the first game Cleveland was threatening to score with Larry Doby on second base and Al Rosen at first and only one out. Vic Wertz was at the plate and he hit a tremendous line drive to right center field. While it appeared that Giant center fielder Willie Mays had no chance whatsoever to catch Wertz’s drive, Mays turned his back to home plate and chased down the ball to make an over-the-shoulder catch. Wertz later described the ball he hit as having the hardest hit of his career. It was a great catch, but the part that is often forgotten is that Mays whirled around and threw a strike into the infield after the catch. Doby was able to advance to third, but Rosen was stuck at first. Mays had saved at least one run and maybe two from scoring. The game went into extra innings and in the 11th, New York’s Dusty Rhodes lofted a fly ball that cleared the right field fence to give his team the first-game win. As a fifth grader listening to the game I heard the radio announcer literally screaming when Mays made the “impossible” catch. As the writer of my book notes, Mays made many great catches in his storied career. But the one in the 1954 World Series will always be remembered for what it was--”one of baseball’s greatest moments.”

By the way, the Giants went on to defeat the heavily favored Indians in four games in 1954. Had Mays not been able to make that catch, who knows what would have happened.

Another great moment highlighted in the book was one that took place during my senior year in high school. It was the 1960 World Series and the school principal set up a television in the wood shop at school. It was his theory that those who didn’t want to watch could study in the library and not be disturbed by those watching the game. As I remember there were more people in the shop than in the library,

The 1960 Series was between the New York Yankees and the Pittsburgh Pirates. There was a time I would root for the Yankees in the World Series, but in 1960 I was clearly a Pittsburgh fan (again due to my liking the underdogs, I guess). The Yankees dominated at the plate in three games, winning 16-3, 10-0 and 12-0. The Yankee sluggers were at work with Mickey Mantle having hit three home runs, and Roger Maris and Bill Skowron hitting two each. Pittsburgh had squeaked out three wins and the event went to its seventh and deciding game. Again it appeared that New York was going to win easily as the Yankees led 7-4 going into the bottom of the eighth. However, Pittsburgh scored five times in the bottom of the eighth to lead 9-7. I can remember thinking those many years ago that the Pirates would probably win. But, alas, New York scored twice in the top of the ninth to tie the score at 9-9.

Yankee manager Casey Stengel brought in Oklahoman Ralph Terry (from Chelsea) to pitch to Bill Mazeroski in the bottom of the ninth. On Terry’s second pitch, Mazeroski connected and sent a drive over the left field wall as Yogi Berra, who was playing left field in that game, watched helplessly as the ball soared over his head and over the fence. Mazeroski’s home run gave Pittsburgh a 10-9 victory. It was the first World Series Championship for the Pirates in 35 years and it was the first time a World Series had been won by a “walk-off” home run. I remember one of my friends there in the wood shop asking the question,, “Who the heck is Mazeroski?” As I recall, he mispronounced the man’s name while asking the question. Terry was rewarded for his part in Mazeroski’s triumphful moment by being declared the “goat” by the New York sports writers. He redeemed himself by being the hero in the Yankees’ 1962 World Series win over the San Francisco Giants.

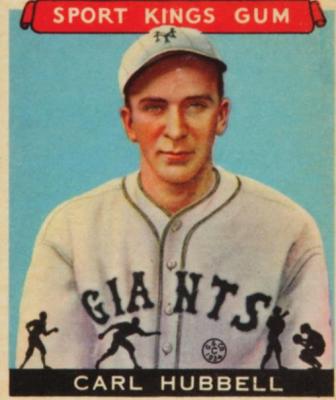

The last event highlighted in the book that I have chosen to share involved the time that Babe Ruth allegedly called his home run against the Chicago Cubs during the 1932 World Series. The book points out that there was much animosity directed towards the Yankees and especially Babe Ruth by the Chicago fans. There was some racial elements to the animosity because there were unfounded rumors circulating that Ruth had some African-American ancestry. When Ruth came to bat in the fifth inning, the Cubs and the Chicago crowd began pelting the Yankee slugger with obscenities and lemons. Ruth made some gestures at the plate and when the obscenities increased, he finally pointed to the outfield. On the next pitch he hit a drive that was later described as the longest ball ever hit at Wrigley Field for a home run. Sports writers claimed that Ruth had called his home run.

There has been many who discounted the claim that he had predicted his long blast, but when I lived in Illinois, I knew a man who had witnessed the event as a youngster. He was utterly convinced that Ruth had called his shot and then hit it out to spite the unruly Chicago crowd. “If you had been there you would have known that he did call his homer,” I heard the guy say on at least a couple of occasions. Being a fan of Ruth’s accomplishments, I choose to believe him.

I have just glanced through portions of my library discovery. I am trusting there will be many other nuggets to glean from it.