New Hall-of-Fame members worthy of honor

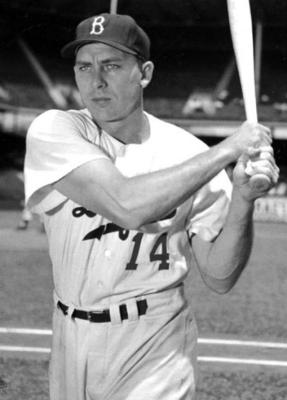

Sunday, the list of persons chosen by the Veterans’ Committees to enter the Baseball Hall of Fame was released. I was elated to learn that Buck O’Neil, longtime spokesperson for the Negro Leagues in Baseball was one that was named. There is probably no one who has done more for the national pastime than O’Neil--all of baseball, not just the Negro Leagues.

I hadn’t had time to rejoice sufficiently about O’Neil’s selection when I glanced at the names of the five others who will join him in this year’s class of inductees. There are some worthy names there as well. Minnie Minoso, Tony Oliva, Gil Hodges, Jim Kaat and Bud Fowler were also chosen.

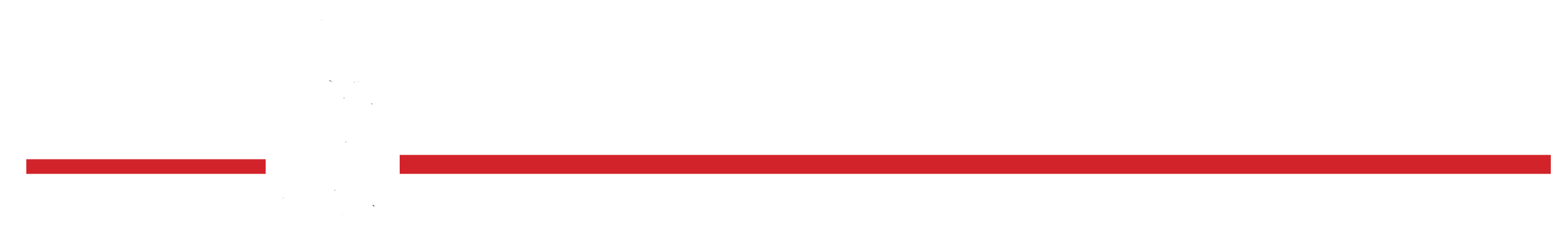

I am not very familiar with Bud Fowler, but I have a good excuse. His career was basically over by 1900 and with my birth certificate I can prove I wasn’t around then. But reading up on Fowler I find he has a very interesting story. He was African-American and is credited with being the earliest known member of his heritage to have played “organized baseball.” Fittingly enough, he learned to play baseball as a child in Cooperstown, N. Y. Fowler played Negro League baseball during his career, but he also played for otherwise all-white teams. His first such experience came when he was 14 and played for a team out of New Castle, Pa. He also is documented as playing for another white professional team in 1877 when he was 19. According to Wikipedia, he pitched a game in April, 1878 for the Picked Nine, as they defeated the Boston Red Caps, the defending National League champions. He went on that year to play for a couple other all-white teams. Fowler was christened John

W. Jackson, but later his family’s name was changed to Fowler. He was nicknamed “Bud” reportedly, because that’s what he called everyone else.

His career took him to many locations, including Keokuk, Iowa, Topeka, Kan., and Pueblo, Colo. The latter three were members of the Western League. In Topeka, his team won the league in 1886 as Fowler hit .309. He moved to Binghamton, N. Y. where racial tensions arose and his teammates refused to play with him during the 1887 season. His career went on into the early 1900s when he was playing primarily for Negro League teams. Again quoting Wikipedia, baseball historian James A. Riley credited Fowler with playing 10 seasons of organized (white) baseball, a record for an African-American Player until broken by Jackie Robinson in his final year with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

The newspaper in Keokuk, Iowa, noted that Fowler was the most popular player on the Keokuk team. In the article, he was described as “hardworking, a genius on the field, intelligent, gentlemanly in his conduct and deserving of the good opinion entertained for him by baseball admirers here.”

Just as an aside, a good friend who is well versed on old time things, has told me that in the days of yore the correct way to spell the name of the sport was by splitting the word “baseball” into two.

But back to my initial reaction in reading about the HOF selections. I have long been aware of the contributions Buck O’Neil made to Baseball. It is only a shame he wasn’t so honored much earlier, at least during his lifetime.

I never met Mr. O’Neil, but he was introduced to the crowd at two games I attended in Kansas City. For both games, as coincidence would have it, replica Kansas City Monarchs baseball caps were handed out to attendees. Buck O’Neil played almost his entire career with the Monarchs and over the years became a Kansas City institution. He never played in Major League Baseball, although his old friend Satchel Paige worked hard to get a team to hire him. O’Neil was a first baseman, but not a power hitter. He only hit nine home runs in his long career. His career batting average was .288 and he had four seasons in which his average was more than .300. His top two years in batting was in 1946 with a .353 mark and 1947 when he hit .350. He also had four seasons in which his average was lower than .260.

O’Neil later scouted for the Chicago Cubs and worked for the Cubs as a coach for a few years. He also worked as a scout for the Kansas City Royals and was credited in getting the Royals some top prospects.

O’Neil became the unofficial spokesperson for the Negro Leagues, working tirelessly to organize a Negro Leagues Hall of Fame and museum. There is a Negro Leagues museum in Kansas City, of which I have never visited, but would love to if the opportunity ever presented itself.

He lived to be 94, dying in October, 2006, just a month away from his 95th birthday. In July of that year he was signed to a contract with the Kansas City T-Bones, a professional team in an effort to get him recognized as the oldest person to play professional baseball. He appeared at the plate in the Northern League All-Star game to draw an intentional walk and then was replaced on the basepaths by a pinch runner. Before the game he had been traded to the Fargo-Moorhead RedHawks for whom he batted. During the game, it was announced that he had been traded back to the T-Bones, which permitted him to appear at the plate again, and again he received an intentional walk, and was replaced. It was later discovered that he was not the oldest player to ever appear in a professional game, but he has the honor of being the second oldest.

The other four who were selected are worthy of the honor. I was a Minnie Minoso fan as a youngster and always took an interest in his career. When he was with the Chicago White Sox one of his teammates was Nellie Fox, and I can remember thinking as a kid that the Sox had two of its stars who had names usually given to girls. When I said something along those lines to my Dad, he pointed out that Granny Hamner played for the Philadelphia Phillies.

Minoso started in the Negro Leagues, playing for the New York Cubans. But in 1949, he joined the Cleveland Indians and then later went to the White Sox. Minoso later became known as “Mr. White Sox,” his teams’ answer to Ernie Banks who was known as “Mr. Cub.”

One reason I liked Minoso was that he was a well-rounded athlete, being one of the fastest players in the league and was a constant threat to steal a base. He made the “Go Go Sox” of the 1950s go. On top of his speed, he had decent power and for a time held the White Sox career home run record.

He was reinstated at age 57 in a bid to make him the oldest player to participate in an MLB game, but when Satchel Paige’s age was finally figured out, it was determined that Paige was 59 when he appeared in a Kansas City A’s game.

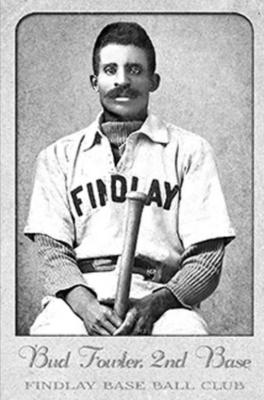

Gil Hodges was a great player for the Brooklyn Dodgers. As a youngster, I always rooted against the Dodgers for some reason I can’t remember and I wasn’t a fan of Hodges’ exploits. However putting all youthful notions aside, I recognize that Hodges was a pretty gifted player. He started out as a catcher, but because Brooklyn had Roy Campanella behind the plate, he was moved to first base where he became one of the best defensive first basemen in the league. He was a power hitter and had more than 300 homers in his career. I remember, when I was rooting for the Yankees in the many Dodgers-Yankees World Series fearful when Hodges came to bat because of what damage he could do with a bat. Later he will always be remembered as the manager who led the 1969 New York Mets to a surprise National League pennant and an upset victory over the Baltimore Orioles in the World Series. He died much too young at the age of 47.

Jim Kaat was a longtime pitcher for the Minnesota Twins. He was a workhorse who won 283 games during his career. He pitched until he was 44 finishing up with the St. Louis Cardinals after 25 seasons in the MLB. He made a successful transition from the playing field to the broadcast booth, where he described games for the Yankees and the Minnesota Twins. I heard him in the broadcast booth on numerous occasions and will say that he was one of my favorite athlete-turned broadcasters.

Tony Oliva was another longtime member of the Minnesota Twins. Minnesota fans have been dreaming for Kaat and Oliva to be inducted into the HOF. Guess what? They made it in the same year. Oliva was a picture book hitter, who was very consistent year after year. I happened to see a game in Minnesota as a college sophomore in 1963 and both Kaat and Oliva played on that day. I remember Oliva got on base with a single and Harmon Killebrew followed with a home run. That was the heart of the Twins offense that year.

I am a happy camper with the old-time Hall of Fame selections.